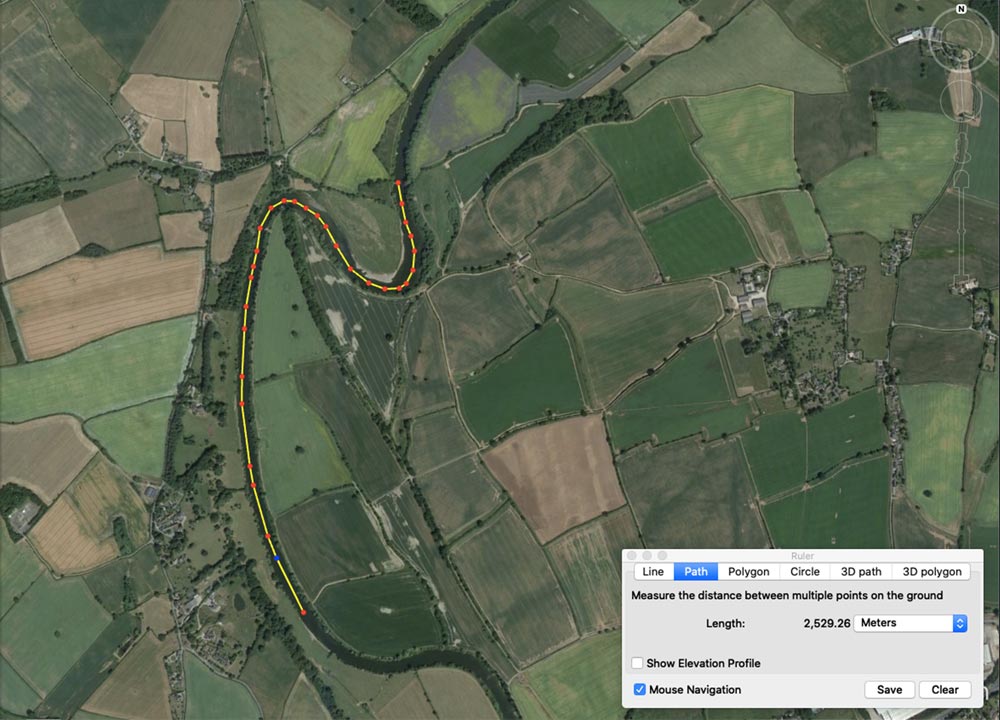

Townsend Farm has 2.5 km of the River Wye frontage, exactly 1% of the total length of the river of which we influence only 50% of this (one side of the river’s catchment).

The Wye, on the border of England and Wales, is a large river representative of sub-type 2. It has a geologically mixed catchment, including shales and sandstones, and there is a clear transition between the upland reaches, with characteristic bryophyte-dominated vegetation, and the lower reaches, with extensive Ranunculus beds.

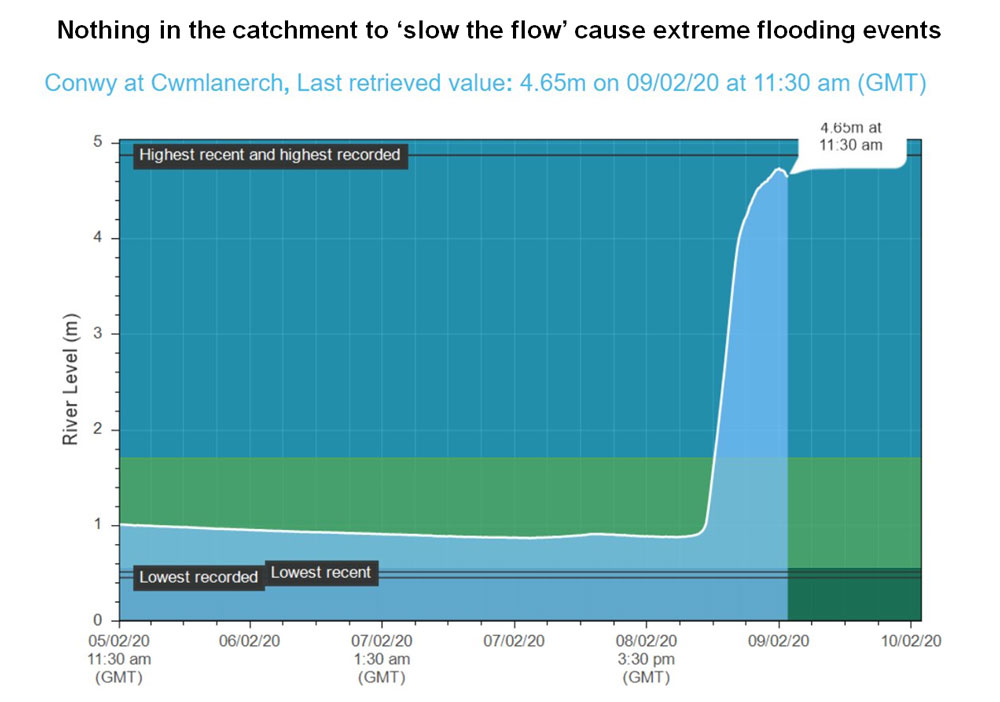

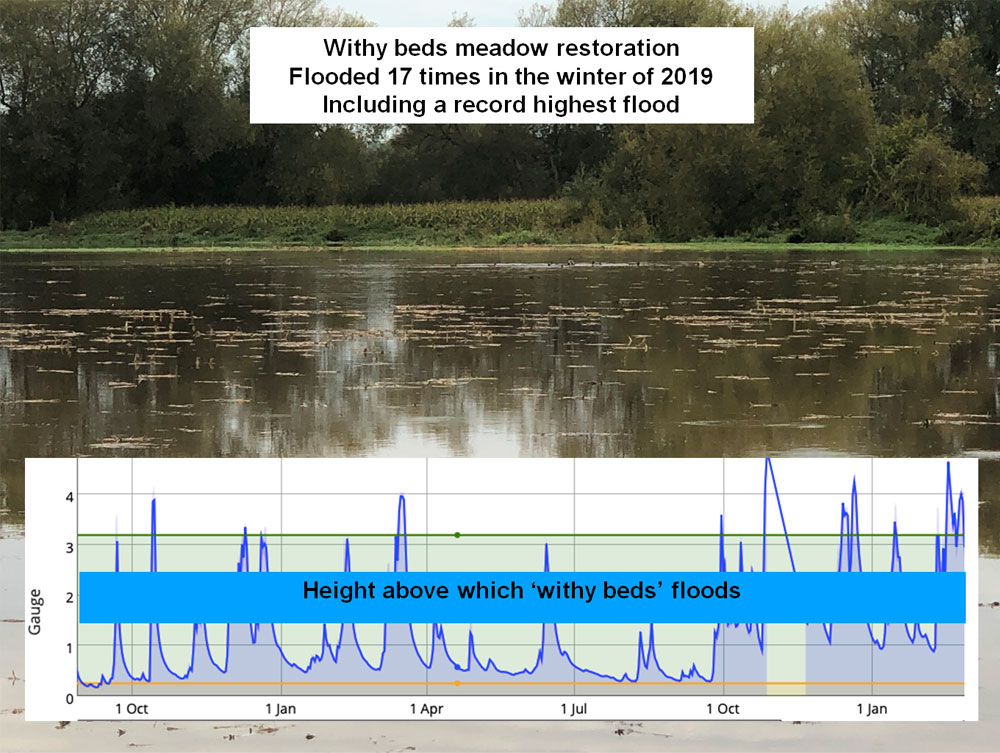

There are more weather extremes in the past 20 years than there were in the previous 70 years!

Hereford Times

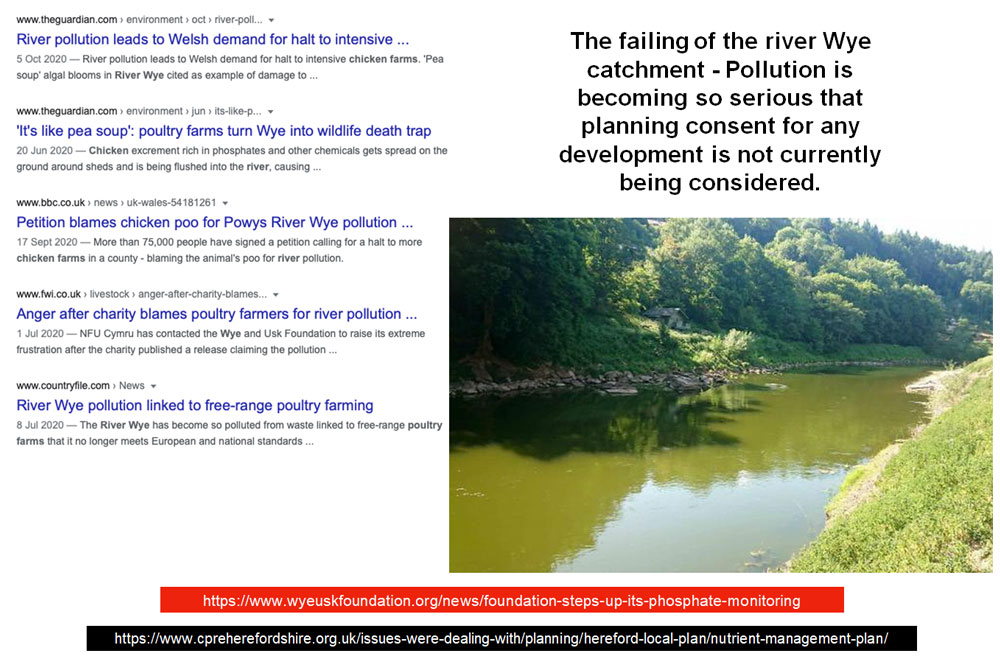

RIVER pollution is the biggest environmental challenge facing Herefordshire.

Phosphate levels in the Lugg and Wye have risen to such levels over recent years that local authorities, government agencies and farmers have been forced to take action.

The high levels of phosphates are mainly run-off from farming and sewage treatment works making its way into the watercourse.

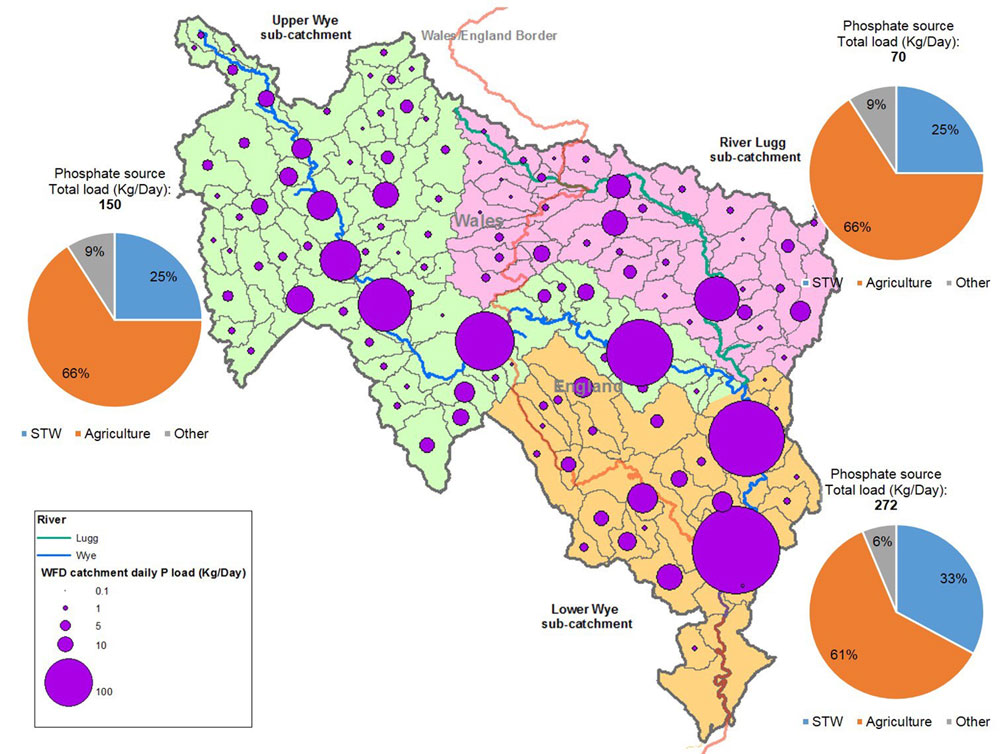

The latest Environment Agency data suggests there is a daily load of 272 kilograms of phosphates into the River Wye.

Of this, about 60 per cent comes mostly through rainwater run-off from agricultural land and farm tracks. While about 30 per cent comes from sewage treatment works and the remaining 10 per cent from other sources.

A nutrient management board was originally set up in 2014 to try to address these issues and improve the water quality in the Lugg and Wye.

Partners on the board include the Environment Agency, Natural England, Herefordshire Council, Powys Council, Natural Resources Wales, Welsh Water, Wye Usk Foundation, National Farmers Union and Countryside Land and Business Association.

But despite their efforts, last year Herefordshire Council put a moratorium on housing development across the river Lugg sub-catchment.

This came after Natural England updated its legal advice following a European Court of Justice ruling known as the Dutch case.

Investments made by Welsh Water have so far brought about substantial improvement in the proportion of phosphate that comes from sewage treatment works.

And councillors expect this will reduce further with the delivery of integrated wetlands that have been the result of investment by Herefordshire Council in partnership with the Wye Usk Foundation and the efforts of local housebuilders who are delivering their own wetlands.

However, in the same period, the proportion of phosphates from agricultural diffuse has increased despite the efforts of the Environment Agency, NFU, CLA and Farm Herefordshire.

Earlier this year, the Wye was affected by the algal bloom, and councillors believe that some of the conditions that produce the bloom such as sunlight and water temperature will become increasingly frequent due to climate change.

The proliferation of poultry units in Powys has also come under scrutiny. Councillors say they are an important element because they are in the upper reaches — the severity of the algal bloom is dictated by the length of time the algae has to divide in the water.

Phosphate is also coming off top-dressed grassland, arable (particularly maize and other bare-soil crops), and from livestock units.

Nutrient management board chairman Elissa Swinglehurst said: “We all need to do our bit to stop this from happening.

“It’s not an impossible task, but we do need to work together as regulators, councils, farmers, housebuilders, water companies to save the Wye and we need to do it now.

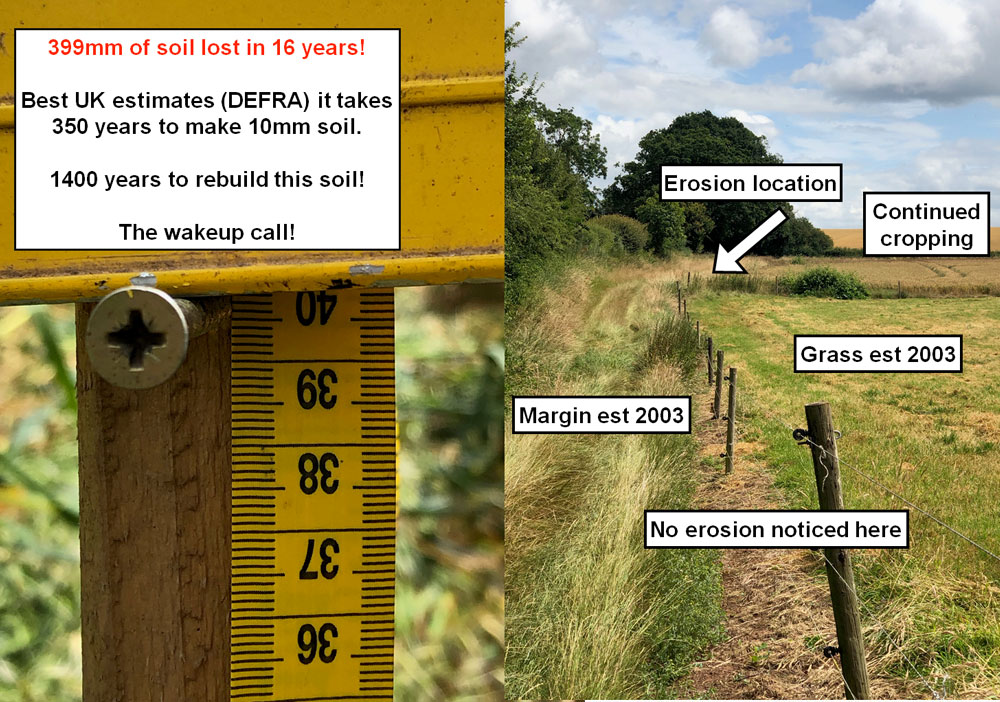

“What I want is that when it rains I will not be seeing brown floods taking soil and valuable nutrient off compacted fields and into the watercourses.“This year, I had fields near me where so much soil washed off it needed a loader to clear a path to local houses. All of the nutrients went straight into a Wye tributary which discharges into the Wye at a point where there is a peak in phosphate levels.

“So many farmers are doing the right thing – they are looking after their soil, taking care of the river, fulfilling their role as guardians of the countryside, but, sadly, some are not.

“I beg those farmers to stop being part of the problem and start being part of the solution.

“For all our sakes, for the sake of the river, the countryside and the future generations who will want to live and farm in the beautiful county of Herefordshire.”

Healthy soil has amazing water retention capacity

1 kg of organic matter can hold 17.3 kg water

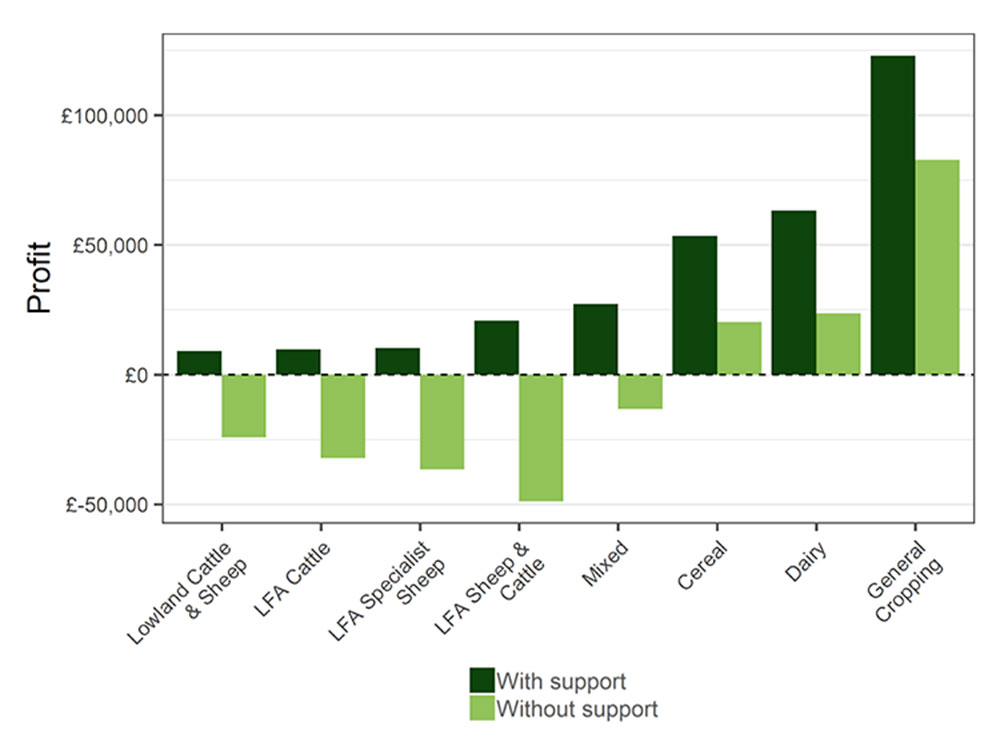

Public money for public goods?

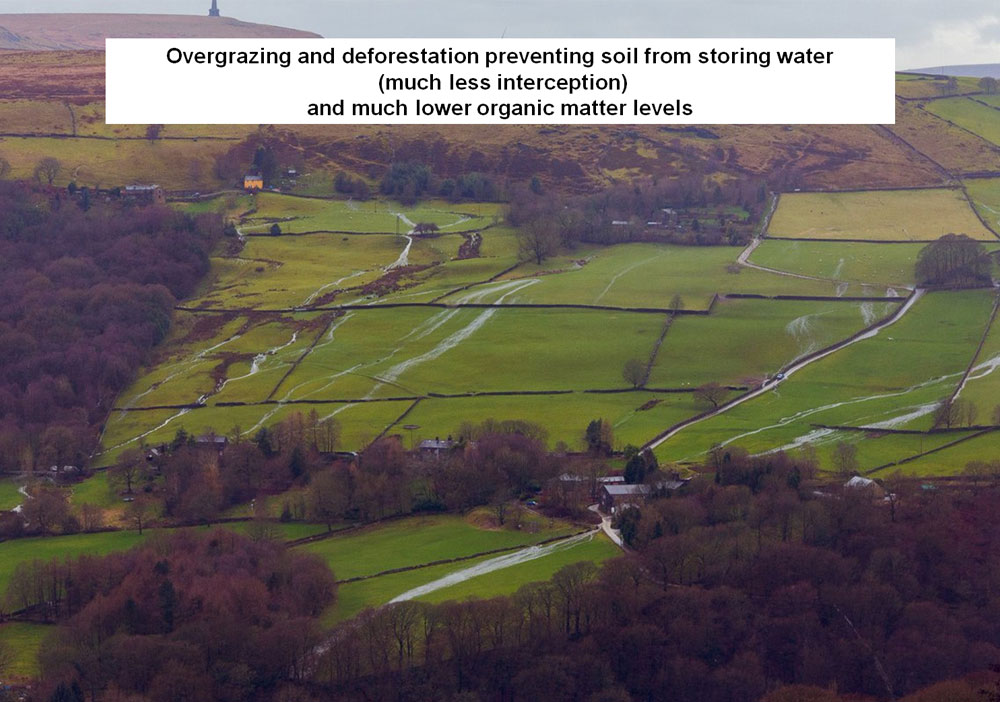

The current farming system supports an industry (LFA less-favoured areas, e.g uplands) that would otherwise be not viable and by supporting it, the environment and soils become degraded to a point that causes river levels to rise rapidly during any rainfall event, causing flooding downstream and damage to properties and businesses, the very people who are paying taxes to support the farming industry!

Subsidy for storing water?

- This would be a better use of taxpayers money!

- Farms to focus on increasing soil organic matter, through regenerative farming techniques.

- To plant hedges, trees and coppices to intercept water.

- To plant buffer strips to prevent any water or soil from leaving the field boundary.

- To use animals to benefit the countryside, not degrade it, through regenerative farming techniques.

- To restore native habitats and hay meadows.

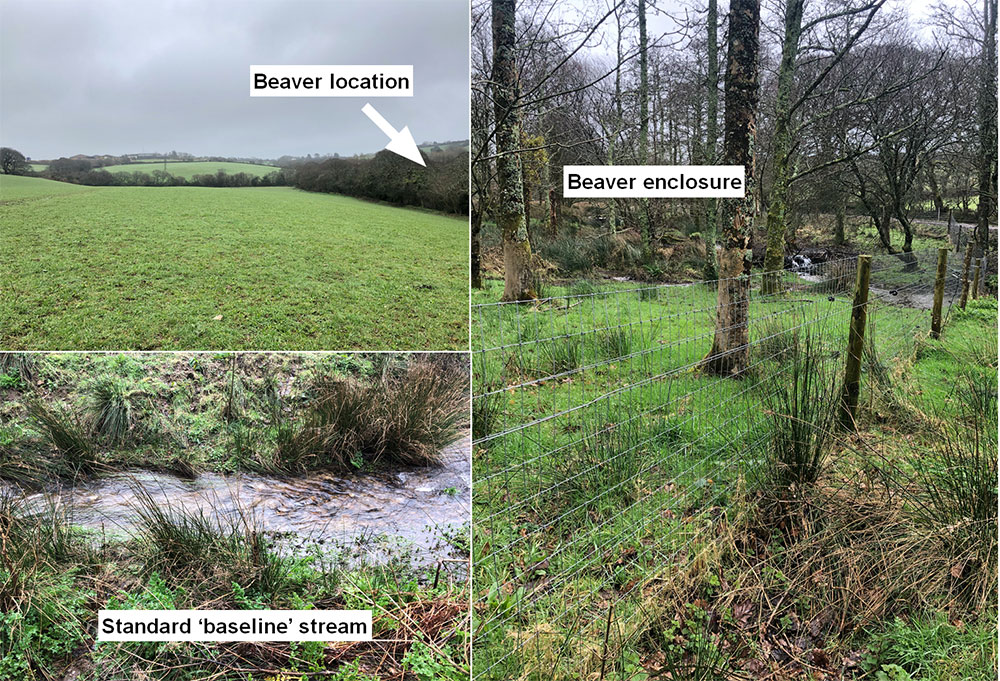

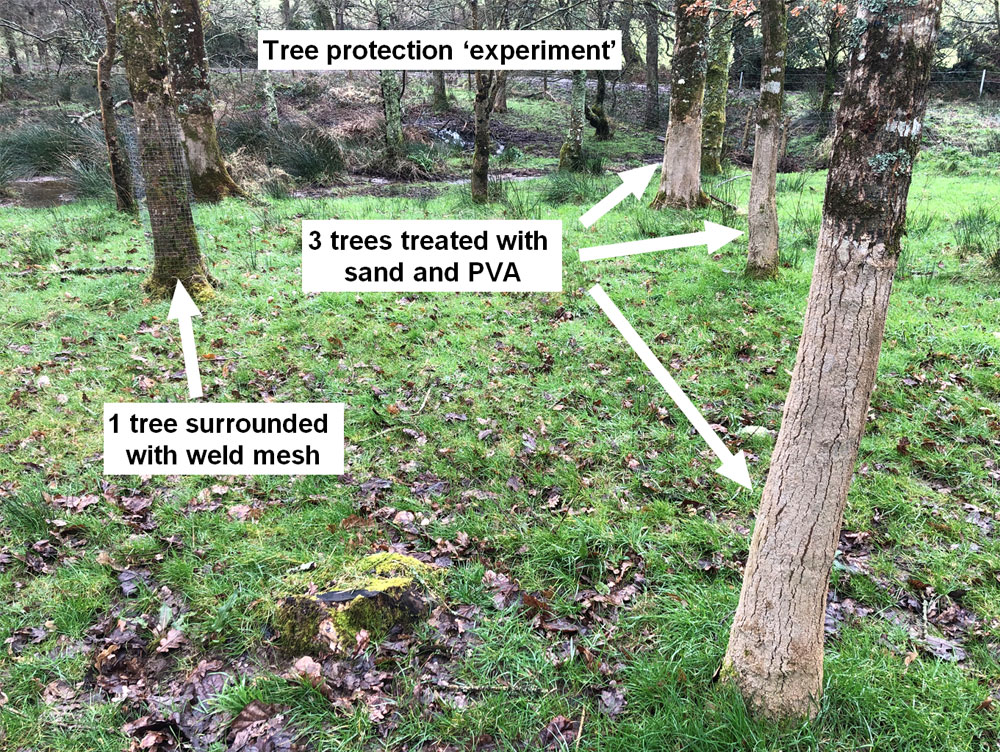

- To promote and provide a living environment for natures very own hydrologists – the beaver.

We face ecology poverty

- Britain is the 29th most nature-depleted country out of 218 in the world and our natural systems are on the brink of collapse.

- We are economically rich yet ecologically poor.

- If all 7.6 billion people lived like people in Britain, then 4 planet Earths would be needed to sustain us.

- We continue to promote economic growth and then ‘off-shore’ our guilt. We save Sumatran tigers while British wildcats quietly become extinct.

Our life support is failing

- Britain is already experiencing climate breakdown – the escalating costs of floods and droughts were £5 billion for the 2015 storms alone.

- Around 5.4 million properties in England are at risk of flooding from rivers and the sea, surface water or both. Annual flood damage costs for the whole of the UK are estimated to be in the region of £1.1 billion.

- Time is running out. Britain has lost almost half its birds, mammals, reptiles, insects and plants since the 1970s.

- While staring down the barrel of just 60 more harvests, we waste 40% of our food and watch our soil wash out to sea.

And yet there is hope

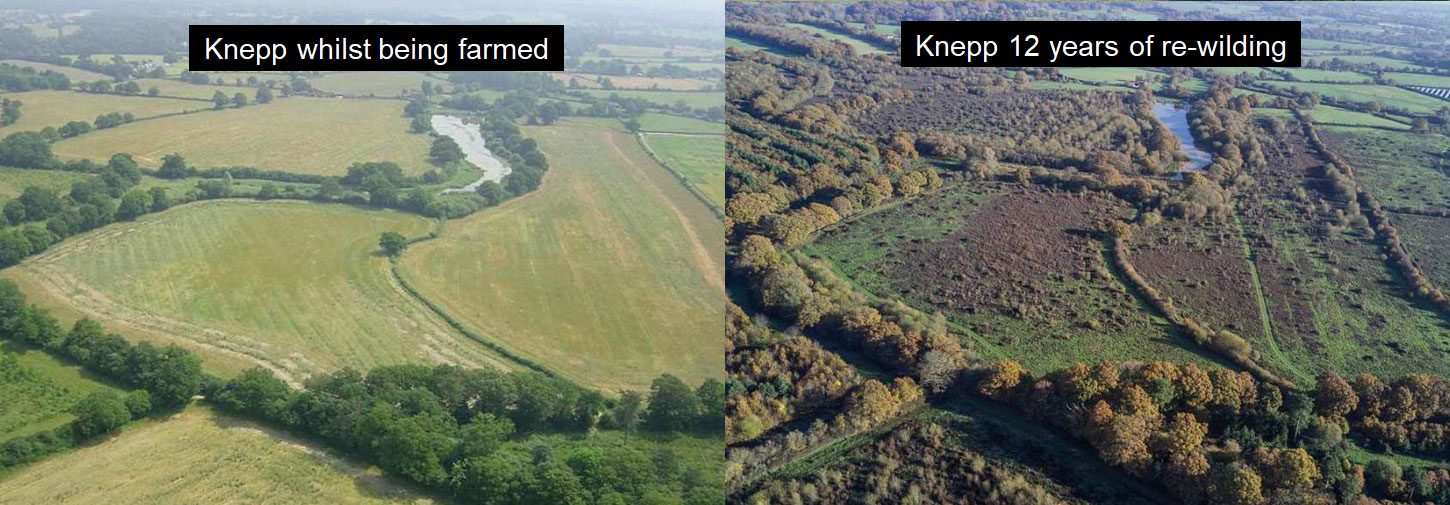

- Nature restoration is not new. There are some great examples of rescuing rare butterflies or birds, or saving unusual meadows or moors. But they have failed to tackle the scale of our national ecological catastrophe.

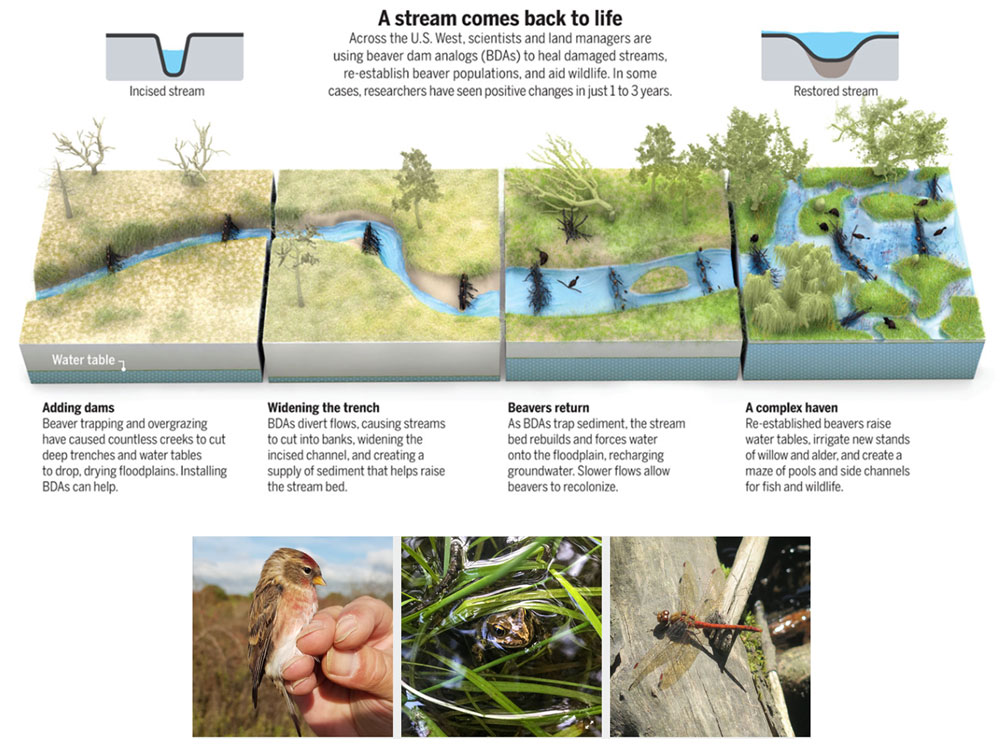

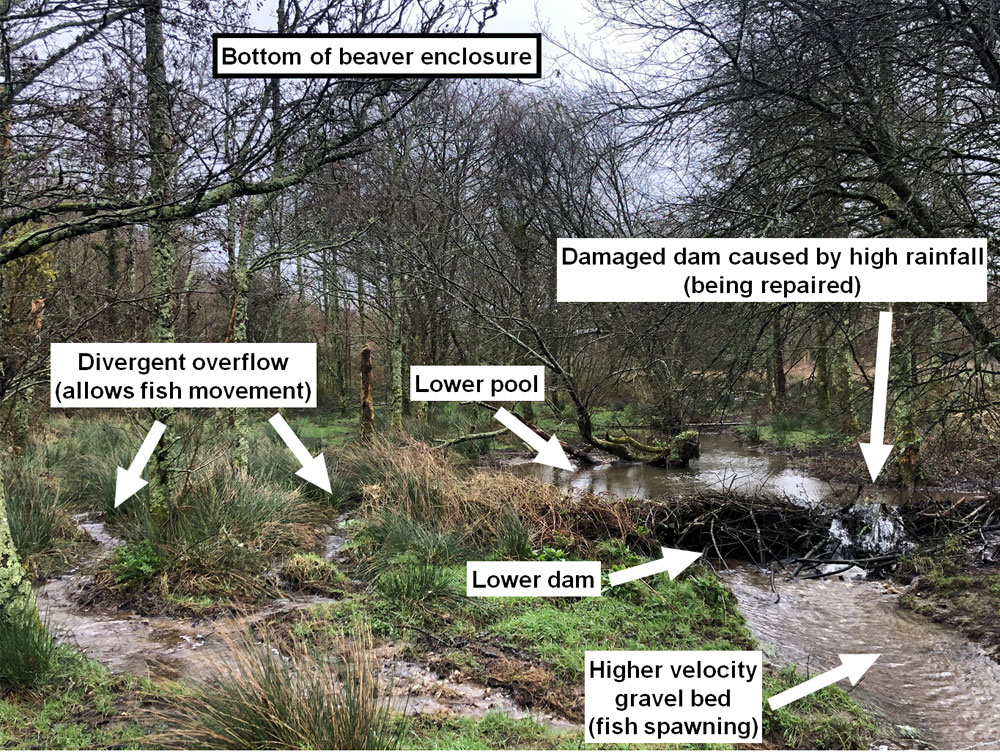

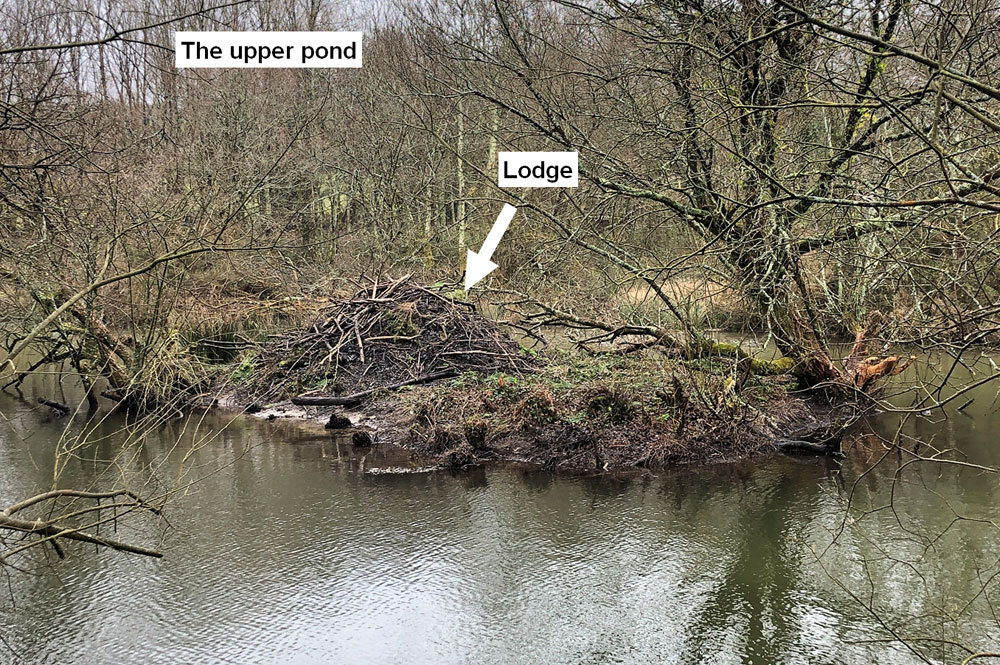

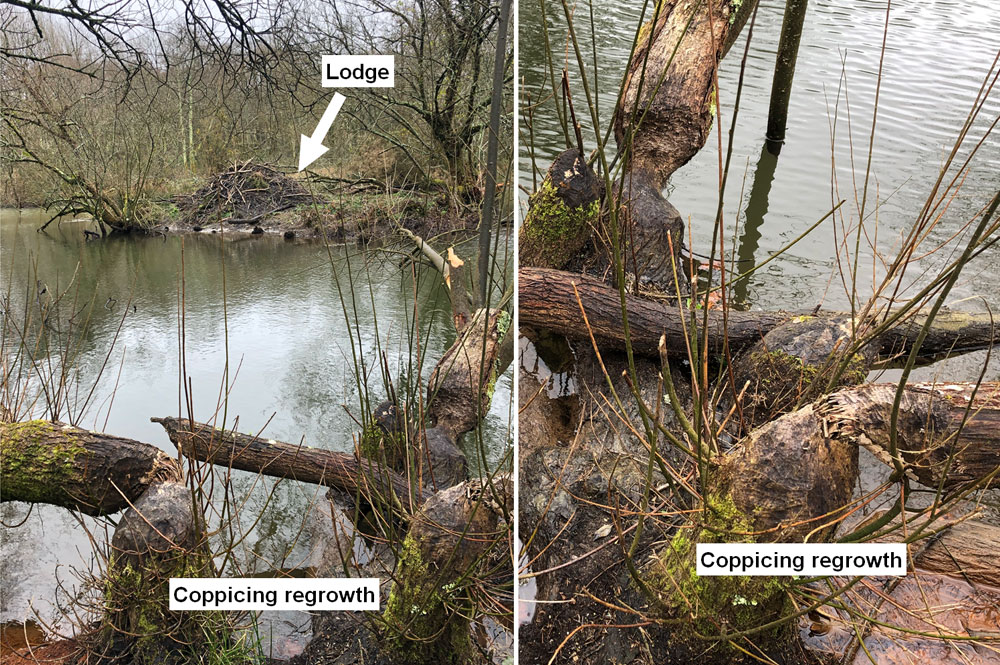

- The dams on our Cornwall Beaver Project at Woodland Valley Farm have reduced flood peak flow rates by over 30%.

- Space for Nature’s Bee Roadzz improve Wiltshire insect corridors and Back from the Brink is saving 20 native species.

Introducing The Beavers

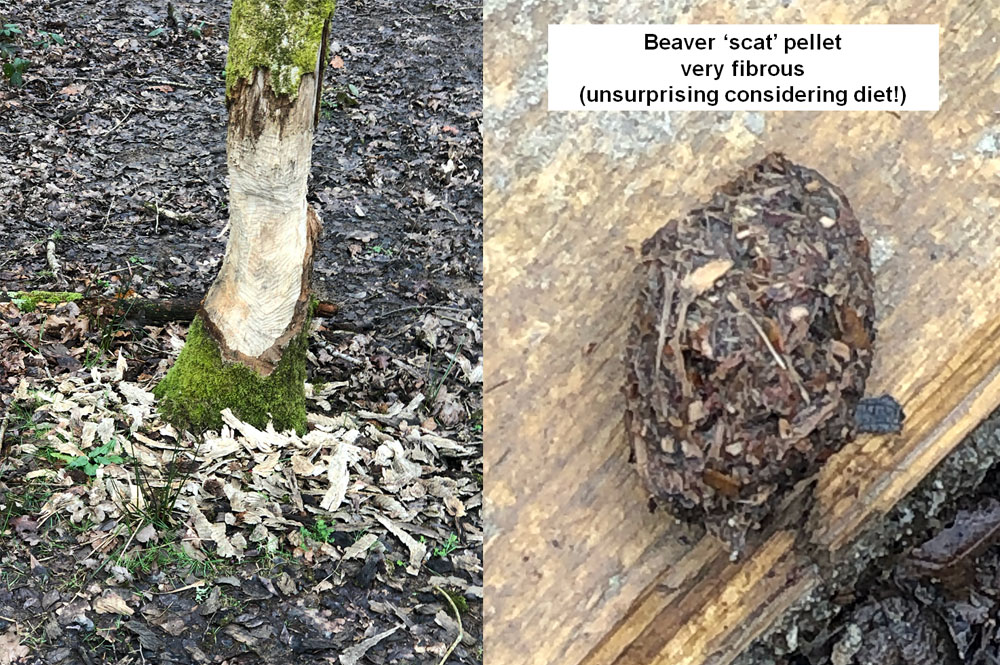

Beavers once roamed across our countryside, shaping the landscape and waterways, providing habitat for a huge abundance of fish, birds and insects.

Native to Britain – beavers once covered the northern hemisphere from North America to the Arctic Circle, including the whole of Britain;

Hunted to extinction – beaver glands contain salicylic acid from their willow diet, which was prized as a medicinal cure-all. A single gland could equal a year’s wage for a mediaeval worker. Their fur is also extraordinarily soft and warm and in high demand for coats and hats;

Evolving alongside salmon – fish and beavers evolved alongside each other for 40 million years.

Part of human history – beaver pools provided early people with places to hunt, fish to eat, furs to wear and plants to harvest.

Beaver Trust’s first programme Mainstream is about making beavers a normal part of our waterscape once again. We encourage farmers, fisheries and communities to work together to restore river habitats using beavers.

Beaver wetlands bring benefits

- Clean water – beaver dams and ponds filter out pollutants such as agricultural chemicals;

- Captured carbon – beaver dams hold back silt that locks up carbon, while the huge amount of new plant growth also forms a carbon sink;

- Reduce flooding – beaver dams and pool systems slow the speed of water flowing through the system and prevent flooding downstream;

- Prevent drought – beaver pools hold water for use in periods of drought;

- Abundant nature– beaver pools provide nurseries for invertebrates, fish and amphibians; while clearings fill with wild flowers, attracting insects and birds.

Natural water engineering

- Beavers are often called “engineers”. Think of all the manmade structures that correspond to beaver technology: dams, weirs, locks, canals. As we return to “natural engineering” to help us adapt to climate change, we can learn from these remarkable animals:

- Approved by experts – beavers are such capable ecosystem engineers that they have been proposed as a tool for implementing the EU Water Framework Directive.

- Our best solution– research by the Environment Agency suggests returning England’s waterways to a good ecological condition could generate £21 billion in benefits over 37 years. Beavers could play a part in helping us to achieve this.

- Huge cost savings– beavers know instinctively what to do and they are highly effective. It’s up to us to work out how to live alongside them and make the most of what they can do.

Healthy rivers mean healthy people

- Beaver landscapes are special places – they feel truly wild, bursting with birdsong, the buzzing of insects, new plant life and sunlight on water. This is good for nature and good for people too.

- Good for our mental health– by immersing ourselves in the unique landscapes beavers create, we can reconnect with nature, and improve our own health and well-being.

- Living alongside nature– we need to remember how to live better with nature if we are to farm, work and live sustainably in the future. Working with beavers can help us open our minds to a new way of collaborating with wildlife.

- Learning as we go– by collaborating with scientists, we will be able to monitor the hydrological, ecological and sociological impacts of beavers. And we will share this with young people in schools and universities. Our work will be open source and accessible to all.

This page is only a section of the full report which you can see in full via the video below.